Gone With The Wind FC: Exploring the past to find enduring truths and market inefficiencies

TF: Please enjoy the return of Jared Young who has brought us this banger of an Absolute Unit post.

In the second stanza of Sun Kil Moon’s song Glenn Tipton the infinitely dissectible character sings, “I like old movies with Clark Gable, just like my dad did.” This sweet sentiment suggests there are artifacts passed down to us from the “old days” that still have value today, and the character finds joy in actively conserving them from generation to generation.

This idea of keeping some things from the past is interesting. We know we don’t know everything as we sit here today. Innovation is critical to our future. But it’s important to keep what we’ve learned to be true, while we quickly discard what we learn to be incorrect, and build from there.

What things should we keep from soccer’s rich history? Innovations in tactics render much of the old ways useless – anyone want to try a 2-3-5 formation from the 30s? Less ancient tactics of deep lying 4-4-2 blocks still have their place for the underprivileged. Some tactics hang around that we can all appreciate. Some are long gone.

Player fitness has long been overhauled with concepts like Periodization. And there’s been more simple changes, like forcing the players to stop smoking.

Soccer analysts avoid the initial findings of 1950s data guru Charles Reep. But a more recent innovation we call expected goals is a building block of past data that is carving out a place in the breakdown of the sport.

What else can we keep from the past besides the memory of the great innovators and formative building blocks that brought us closer to the soccer truths as we understand them today?

As this newsletter examines how soccer organizations can use tools from the financial industry, philosophy and other disciplines to make better decisions and improve the performance of their club, I’ll posit the past can tell us something about the cost of a goal – and from that a framework for constructing rosters and drafting contracts to maximize the number of goals a team can take from another.

Movies with Tommy Lawton and Clark Gable

In 1939 Tommy Lawton’s 35 goals led Everton to an English First Division title. Lawton was likely paid the maximum wage allowable per week in 1939, of £8.

Not long after Everton’s title, the concept of blockbuster entertainment was forever changed. The movie Gone with the Wind starring Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh became a global sensation. The movie took in a record $390 million at the box office. Since tickets were around a buck back then, it’s estimated that 400 million tickets were sold, equating to a ticket sold for every six people on the planet.

Clark Gable reportedly made $120,000 to make the film, or 3 basis points of the ticket revenue.

Movies with Mohamed Salah and Iron Man

Fast forward to 2018 and Mohamed Salah’s scintillating 32 goal campaign for Liverpool. Salah didn’t land Liverpool a title, but he still earned a wage increase to roughly £200,000 per week – a mere 25,000x more than Lawton. “Inflation!,” you might be thinking. But, no. Inflation in that period in the UK only accounts for £544 of the £199,992 increase in pay between the two forwards. Something else is going on here.

Not long after Salah reached Superhero status, Avenger’s: Endgame hit theatres and grossed a monstrous $2.8 billion at the box office. Approximately 290 million tickets were sold worldwide, or one ticket for every 25 people. Endgame didn’t reach the world like Gone with the Wind, but it still made more money even after adjusting for inflation.

The character behind Iron Man, Robert Downey Jr, was paid $75 million to make the movie, or 267 basis points of the ticket revenue. That’s 625x what Clark Gable made in terms of revenue generated.

And that example is dated to align with the movie release. Since then Kevin de Bruyne makes £375,000 per week, and Salah later signed for almost double the amount at £350,000 in 2022. Even with inflation at an annoyingly high rate, prices haven’t doubled in five years.

So then, what’s all this?

The Outsized Growth of Entertainment

The economy of entertainment, and especially the realm of sports, has far exceeded the growth rate of inflation and the income of the average person. It’s also been growing like this for a long time. And, increasingly, the stars of soccer are getting a bigger share of the pie. Below is a chart of the ratios of inflation and wages in the UK and US since 1939.

Movie tickets in the UK have outpaced wage growth but the wage paid top players in the EPL doesn’t even fit on the scale for these numbers.

Even selecting a more recent time period the growth of soccer is mindbogglingly fast compared to any normal looking economy. Starting at 1996, Major League Soccer in the US now appears on the chart. MLS growth rates are outsized due to two factors. The first is that 1996 was the first year, so initial values were at their lowest point. And the second is the league’s structure focusing on Designated Players, which allows more spending on the league’s best and most expensive players.

Movie entertainment has outpaced incomes but only marginally, but the soccer bars jump off the page in terms of massive growth. And in the case of the English Premier League, we are looking a relatively mature business over this timeframe.

Goals Do Not Grow

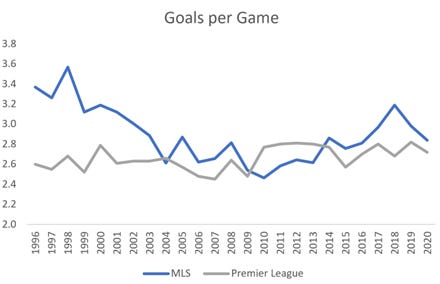

In contrast to the fantastic growth on the money side of the game, goals scored in a game do not seem to grow at a similar pace. In fact, goals are down in the English top flight since 1939, when they were 3.07 per game, and they’ve been jumping around between 2.4 and 2.8 goals in the Premier League now for a few decades.

Major League Soccer has been more volatile as they have found their tactical way, but as expected, the game largely remains the same as in the EPL.

What this means of course, is that the cost of a goal is rising at a rate that is much faster than we might perceive. Given that goals are a zero sum game – a goal scored for one team is a goal lost for another team - the cost of creating a net goal is getting exponentially more expensive.

Introducing Gone With The Wind FC

In honor of Tommy Lawton and Clark Gable, welcome to the front office of Gone With The Wind FC, where we look at historical financial trends and factor them into the decision making process. The name reminds us of how quickly things can change, so we can better prepare for the future. But it also reminds us that some trends have been going on since the beginning of blockbuster entertainment.

Gone With The Wind FC is a league agnostic club, so we need to be able to adapt to the financial structure and trends for each league. To that end we need to think in terms of frameworks and theory, so as to be able to adapt, no matter where in the world we play.

The economic trends will lead us to explore two distinct concepts – how to look at historical cost and goal data to find competitive advantage when constructing a roster, and anything that might teach us about structuring contracts.

The data on top class players is that in absolute terms their salaries are going up more quickly than the average player, creating a growing inequality, especially in Major League Soccer in the US.

Here’s a view of that in MLS where wages are readily available at an individual level.

All players are getting more expensive, but the top players are getting even more expensive. But are those same top players also becoming more effective in creating net goals? One of the benefits of focusing on MLS is that the statistical hounds are public and active here. American Soccer Analysis has published a “goals added” (g+) statistic that attempts to score each player’s ability to create goals. Let’s look at that relative to salary growth.

We talked about being theoretical. Let’s have some fun. Let’s assume that we at Gone With The Wind FC are perfect Sporting Directors. We never miss on a talent. Our scouts can predict goal creation with 100% accuracy. We pay players exactly what they are worth, to the penny. Perfect Moneyball. We’ll also need to assume that ASA’s goals added score holistically captures net goal creation and is perfect as well. Lot of assumptions.

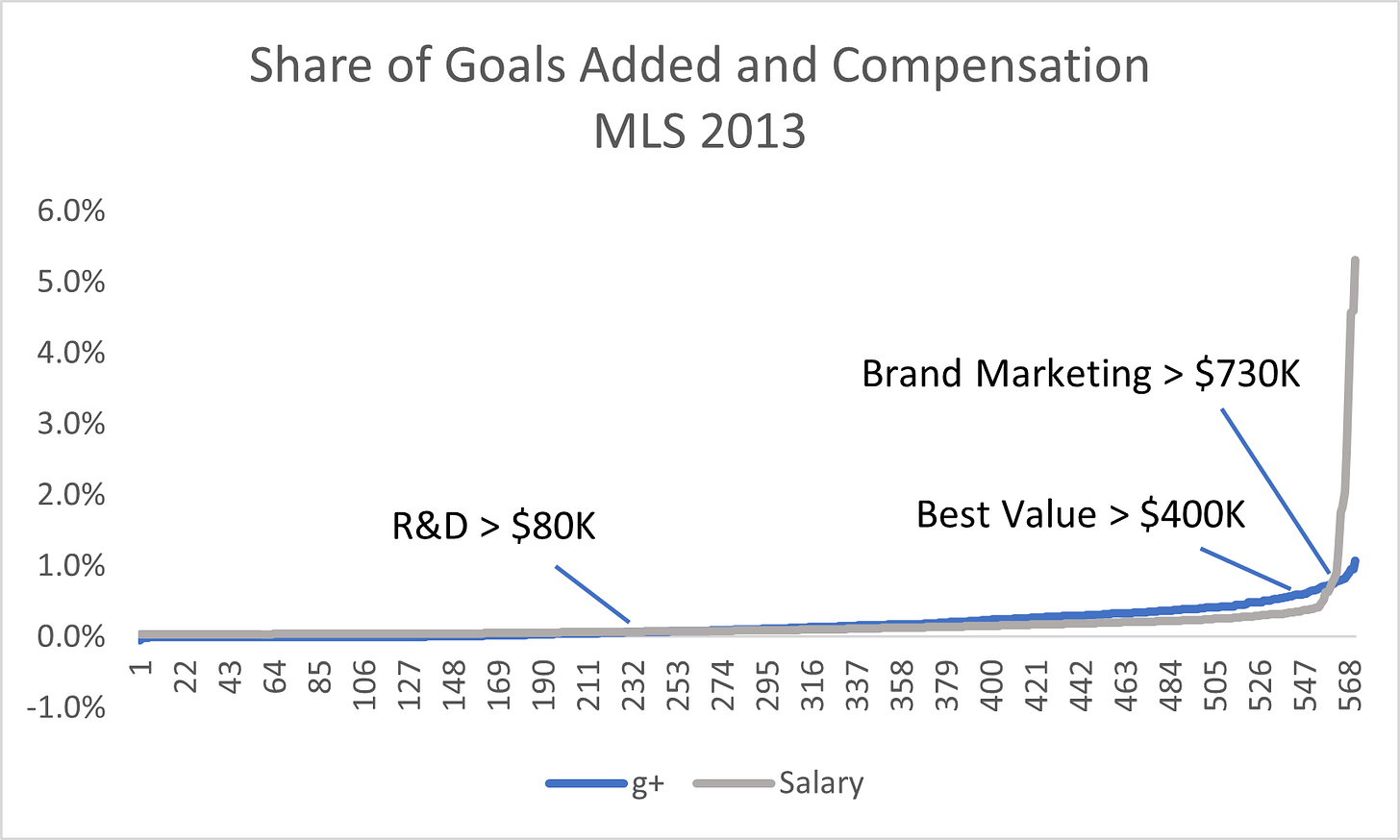

Here’s what that player level plot looked like in 2013 in MLS.

Here we are looking at the share of goals added and total wages paid as a percentage of the total and sorted to line up together for all of the players in the league. This highlights not exactly reality, but what it would look like if a team got it perfectly right, paying the least for the least goals, and the most for the most goals. The goals added numbers and salaries are all actuals from 2013, but the players are mixed up as if everyone was appropriately paid for their production.

Let’s look at how these lines interact with each other and break them down in terms of business practices. When the salary line is higher than the goals line, that means a team is paying an outsized portion of wages relative to the value they are getting in return. And when the goals line is above the wage line a team is getting more value than what they are paying for.

The lines in the chart above intersect in two places, and here we can delineate certain types of business investments. The first intersection denotes the Research and Development section of the roster. The 2013 cutoff for this level turns out to be about an $80K salary. This is the portion of the roster where the team are investing in young or unknown players that aren’t really impacting the game. In a traditional business this would be done in the R&D department. Lots of investment being made with no known short-term benefit, but over time some players will emerge and contribute to the team’s goal creation.

The next point of intersection we’ll call the Brand Marketing line. This is the point at which the salaries outweigh (by a lot it turns out) any feasible breakeven in terms of share of goals added. The lines really start to separate. From a company perspective this is where Brand Marketers come in. This is the budget spent on billboards and TV commercials that aren’t put in place to directly drive new customers to the door, but make people aware of the brand. The top paid players in the league can be thought of this way. They are the headliners for the company, and they have to be, because in MLS there no obvious way they could actually earn their wage in terms of goals.

We could spend a long time hypothesizing why the top paid players in the league don’t contribute the appropriate rate of goals. The transfer race for the best players is intense. Top talent is rare, and bidding intensifies like this for scarce talent in many different industries. Champions Leagues are also to blame. The top teams not only need to have the best players to win their league, but they simultaneously compete against the other richest teams around the world. Between the multiple tiers of competition and any brand value brought the club, teams seemingly have to spend more than a player could reasonably be worth on the pitch on a game by game basis.

But it’s these loss leaders in a business that creates the competitive advantage opportunity. If we’re going to invest budget in R&D and Brand Marketing units with less certain on the field returns, then we should make an outsized gain in the core business, creating goals. In 2013 the optimal level of player, the max difference between goal share and wage share, was one worth $400K per year. Theoretically putting together a starting XI of $400K players for $4.4M would be the ideal approach from a goals perspective. It would be a team without headlines and billboards, and little R&D for the future, but it would give the club the most efficient goal difference possible.

This manner of perfect roster building will certainly have it’s detractors when we loosen these assumptions. So let’s add a dose of reality. It’s obviously very difficult to determine exactly how many goals a player will produce. The uncertainty introduces risk, which of course has a price. The other reality is that there will be some reversion to the mean. The point here is that not all top paid players will have great seasons, and not all low paid players will only be for R&D. And to simplify the view we can look at the players in five segments ranked by their wages.

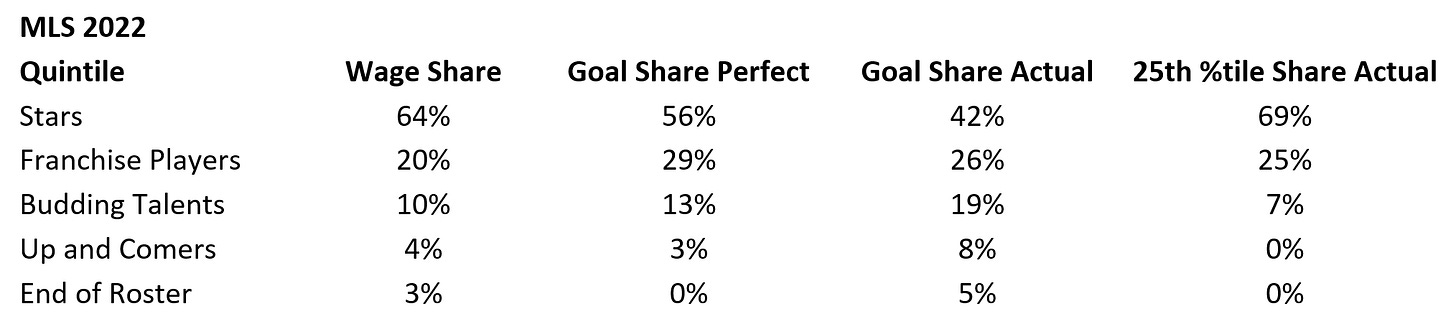

I’ve taken the liberty to label each quintile of players, starting with the highest paid to the lowest. The “Stars” are in the top 20% of wage earners. The “Franchise Players” are next, followed by “Budding Talents”, “Up and Comers” and the “End of Roster” players that will rarely get minutes.

The Stars earn 60% of all the compensation paid in the league. If they perfectly captured the top 20% of all goal creators in the league, they would capture 58% of goals added. However, they only create 33% of goals added, meaning they don’t pull their weight from an efficiency perspective. The last column is an attempt to look at the low end of each segment’s range. The last column looks at the actual goals created of the top 75% of players in that segment. This is an attempt to remove the disaster signings, the injured players, and look at the segment through a risk lens. The Stars look better as you’d expect, but still don’t match the value they cost.

When looking at this the Budding Talents jump out as a great segment to find goal value. This is the range of salary between $150K to $350K in 2013. It also turns out that the R&D segment isn’t so bad. They at least earn their share of goals, but need to avoid the bottom part of this segment.

If you only signed a roster of Budding Talents you probably couldn’t field a competitive roster, so you’d have to move up the scale, and Franchise Players still look quite good. They produce 28% of the goals while consuming 18% of the wages. And there’s not a ton of risk in that segment as the top 75% of the segment captures 50% of share.

Loosening some assumptions there is still clear competition advantage finding players between the 40th and 80Th percentile of wages in the league. This is because of the R&D department, but also the Brand Marketers, who need Stars to raise the brand of the team, and to perhaps make a difference in higher levels of competition.

We’ve been staring at 2013 for a while now. What’s with the old data? This whole post is about examining how things change over time. Here’s a look at the same data in 2022.

The two lines still intersect in the same way, denoting R&D and Brand Marketing investments. In 2013, only 2% of players qualified in the Brand Marketing segment. That group is much bigger in 2022 at 7%. Not surprising, as star players are getting paid more and more.

The average salary for the different levels have essentially doubled since 2013, also as we might expect.

When looking at the table, the league has gotten slightly better at selecting Star players. At least the downside isn’t as bad. But what’s notable here is that the distributions are roughly the same. This same pattern of value creation still exists a decade later. Franchise Players and Budding Talents create 45% of goals and cost just 30% of the wages.

Because these two additional types of investments are so foundational, and the demand and salaries for scarce star players so high, there is consistent value to be found in that key zone.

From the perspective of Gone With The Wind FC this framework needs to be analyzed based on the league in question. MLS has it’s own unique roster rules, and each league’s dynamics will be slightly different. But the shape of the wage share curve is likely to have this same explosion as we near the top of the league. This shape is exactly what gives moderate spending teams the opportunity to find goal creation value at the right level.

Growth Rates and Contract Lengths

We know that humans struggle with the comprehension of compounding growth. We are biased toward certainty in the now, versus any greater value we might perceive in the future. Similarly, sports fans are probably not grasping exactly how rapidly the industry grows and the dynamics are changing from a salary perspective. There is an interesting trend in the world of contracts that is worth looking at given the subject at hand.

In baseball, the most advanced sport from an analytics perspective, there have been 47 players signed to contracts of 10 years or more. There are a handful of reasons for doing this, but one might be an arbitrage opportunity where teams can play off the human biases of a player – offering them long term certainty in exchange for a wage that trends would suggest to be a great value in the out years. These longer term contracts are focused on young, up and coming stars in a sport where value is far more measurable than soccer. Baseball teams can predict with reasonable certainty the production of that player over time, but also know that the value of a run created is becoming more expensive rapidly. If a player in year 10 of the contract is even 90% of the player they project, they still expect that player to be offering tremendous value.

Meanwhile, the player is offered a massive guaranteed deal. The lure of locking up your financial future is traded off for some value back to the team in the out years of the contract.

We recently saw this play out in the NFL. Patrick Mahomes signed a monster 10-year deal in 2022. That was the 6th such contract in NFL history, all for quarterbacks. The stars aligned perfectly for Mahomes and Chiefs. The quarterback had established himself as the best in the game, and with quarterbacks playing later and later, a 10-year deal makes great sense for both sides. Mahomes has the large deal, and the Chiefs will almost certainly have the best quarterback in the league a bargain rate towards the end of the deal. Are their risks on both sides? Of course.

The same logic may have been in place when Chelsea signed Endo Fernandez to a 9-year contract and Mykhailo Mudryk to an 8.5-year deal before the 2023 season. They’re both young and already proven commodities to some degree. Chelsea has stood out for the length of their contracts in recent signings. The amortization of signing bonuses is likely a factor, being able to stretch transfer fees over a longer time period, but coupling this with young star players means they stand to potentially get value for their production as the cost for goals goes up over time.

So what about Gone With The Wind FC? To the extent we believe we are better at identifying talent than our counterparts, we are very interested in locking that capability over as long of a time horizon as possible. Bring on the 10-year contracts. Staring at a better than average 24-year old driven goalkeeper who should easily be able to play into their mid-30s? How’s a 10-year deal sound?

Even if the relationship sours the contract will be attractive to the next suitor, or they can simply negotiate new terms. Might our budding goalkeeper want to sit out when he or she realizes they are underpaid? It’s possible. That happens plenty in sports. Players do have leverage, but that is part of the risk.

However, if you play the game of traditional shorter-term contracts you lock yourself into market rates, and can’t take advantage of the quickly rising cost of goals. You’re just a market taker. If you become a club known for giving longer contracts you might find yourself attractive to players and just might also find some good deals long term.

The counter to all of this is just how unpredictable that age curve really is. There is a long history of bad contracts where players deteriorated faster than expected, or more likely their leverage forced the team into a late contract overpay. These longer contracts have to be given out judiciously, there is no doubt. But outside of Chelsea this trend is not really one that has picked up steam in soccer, like it has for other sports.

Theory is always better when exploring an example. So let’s create a player and put them in the English Premier League. I’ve compiled the wage and table results for the last 7 seasons. Unlike Major League Soccer where wages and winning have very little correlation, the Premier League has a very strong correlation. If you’ll allow me some liberties and short cuts, I’ve created the following linear curve that looks at the per player value of a goal created, in this case goal difference.

To interpret this line, the market says that a player making $7 million should buy a team 2.5 goal difference for the season. It’s worth noting for a late night ponder that this wage to goal difference best fit curve is linear, unlike the wage curve we reviewed above. Predicting goal difference using wages is linear. Actual wages are nonlinear. But let’s not stray too far.

So our Premier League player Rhett is 22, and let’s assume we feel ecstatic about this midfielder and GWTWFC projects they have 10 years ahead adding 1.4 goal difference per season. His current market value is $5 million per season based on the last few seasons. We want to keep this kid around as long as possible - an academy kid and the fans are going to cheer for their entire career. Star potential is possible but the current projection isn’t quite that high.

For the sake of this post let’s offer Rhett a 10-year contract and top off the market rate at a 10 percent premium. This is a $55 million contract for a 22-year old and we’re locking in a club legend.

We’re also increasing our chance of adding 5 to 9 goals over the next 10 years, just based on the contract alone.

Based on the data we’ve reviewed, the math works out that the cost of a goal in the Premier League is increasing 7% a year. By year 10 of this contract the cost of our midfielder’s production will be $9.2 million, well below the $5.5 million he’ll be paid. We can reinvest that savings into an improved roster. By then, that $3.7 million saved will be buying 4.1 goals for the team. Over the course of the contract, we can reinvest the market difference and get 13.8 goals.

But we have to assess this against a more traditional market alternative. Perhaps we could chunk it up into two 5-year deals. This takes some risk off the table, but also will force us to pay our midfielder the market rate in year 6. If you assume that we only pay market rate at the time the contract is signed, and it’s a linear payout after that, then the 5-year deals are still worth 8.3 goals over the 10 years.

If we assume an even more standard 3 contracts over the ten, the advantage drops to 4.6 goals. Longer term contracts still serve their purpose but the longer the better given the rate of change.

Are there downsides to this approach in terms of measurement risk and the risk of a player holding out to get a market rate contract later in their career? Of course, but those need to be assessed any potential gains from simply trying to play this game. Is Chelsea on to something beside just stretching our transfer fees?

Gone With The Wind FC Final Thoughts

Whatever we think we know about the cost of a goal, it’s going to change more rapidly than most of us are comprehending. And that appears to be especially true when staring at the race for star players. But for the frugal and long term minded, these seemingly interminable trends create an opportunity for competitive advantage.

In the final stanza of Glenn Tipton, the lyric goes, “Place ain’t the same no more/Man, how things change.” The character is certainly on to something. For those that run a soccer organization, it’s best to anticipate these changes and take what advantages they offer. For the rest of us fans, we can only sit and debate whether we like the new game and the way it’s being managed, or would prefer to watch some relics of the past.