Theory of Soccer: Options have Value

Zone-reads, pick 'n rolls, cut-backs

While this is squarely in the late “Theory of Soccer” line of posts rather than the classic “corporate finance as analogy to building soccer organization” series of posts that began this blog, I’m going to make that very difficult to believe at first.

So Corporate Finance 101 in a nutshell is basically these 5 things (you’re about to have a BS in finance).:

Time Value of Money & Discounting - having cash today is better than receiving the same amount next month, because of the opportunity cost of what that cash could earn you over the course of the month. From a value perspective, we should “discount” the next month’s return relative to having cash today. If someone wants your cash and promises to pay it back to you next month, you haircut what you give them today, or you make them add interest to what comes back to you next month. You make them add interest (or you hair cut what you give them) until you are indifferent between holding cash and holding a receivable for more cash next month. This is a “net present value” of zero.

Risk-free returns vs other returns. If someone offers to take your cash this month and pay it back to you next month, they need to pay you more interest than you can get from a federal government bond because there’s no risk the federal government won’t pay (they print the money), but there is risk this other guy won’t pay (he doesn’t print money). Risk requires a higher expected return. At the end of the day, you would only accept his offer if he’s promising to pay you enough to compensate you for the fact that he may not and you can get a risk-free return elsewhere. He raises his offer until you are indifferent. This is a “net present value” of zero.

Portfolio Theory — if the efficient market hypothesis is correct and the riskiness of returns are baked into all the prices, and because the returns of different assets covary with one another in different and counter-veiling ways because portions of their industry or company specific risks are opposite one another, then as an investor, on a risk-adjusted basis you can maximize your expected returns by holding a portfolio of all the assets. Some may boom and some may bust, but you’re less vulnerable to those specific risks and accept only overall market risk, instead of picking individual investments and living with both specific risks and overall market risks.

Weighted Average Cost of Capital and Net Present Value for decision making. The mirror of you as an investor, choosing what assets to hold and when… If instead you’re a company which uses capital in order to fund income generating activities, then you’re by identity paying your debtors and your shareholders some sort of return in order to have acquired the assets you need to generate said income, then part of what running a company is.. is you need to make decisions about how to use these assets (go and no-go’s on projects) which return the same as or more than (taking into account time value and discounting and risk above and taking into consideration tax effects) the returns you’re paying your debtors and shareholders. Selecting “positive net present value” projects increases the value of your company $ for $ while choosing “negative net present value” projects decreases the value of your company $ for $. If you undertake projects with “net present values” of zero, the value of your company holds.

Options have value — While you could buy an asset now for $10, it’s better to instead have a legal right to buy (or not to buy) that asset for $10 over some future time horizon (an option). That way if the price of that asset goes up, your return is the increase in price from $10 on, but if it goes down, your loss is zero. Having an option like this is such a good deal that you have to pay for it (called an “option premium.”) After you’ve paid the option premium, in theory your net present value is zero.

It’s really that last key corporate finance principle that I want to use as a jumping off point: Options.

As far as I can tell, across most sports (and most games), the way you win (or the way you score if we were to focus purely on the offensive side of the ball) is in large part by offering more threats to your opponent than they are able to defend. First, it is possible of course to be so much better than your opponent at some basic task that from the first whistle, you are offering more threats than your opponent is able to defend. This can happen if you are just a physically better team for example.

Imagine two American football teams and one of them has big strong offensive linemen and the other has very small weak (relatively) defensive linemen. Running with the ball behind an offensive line where each stronger lineman picks out a weaker defensive lineman and overpowers him is going to work really well. But what about when the teams are even-strength, or perhaps.. what if the offensive team is worse than the defensive team, what is there to do?

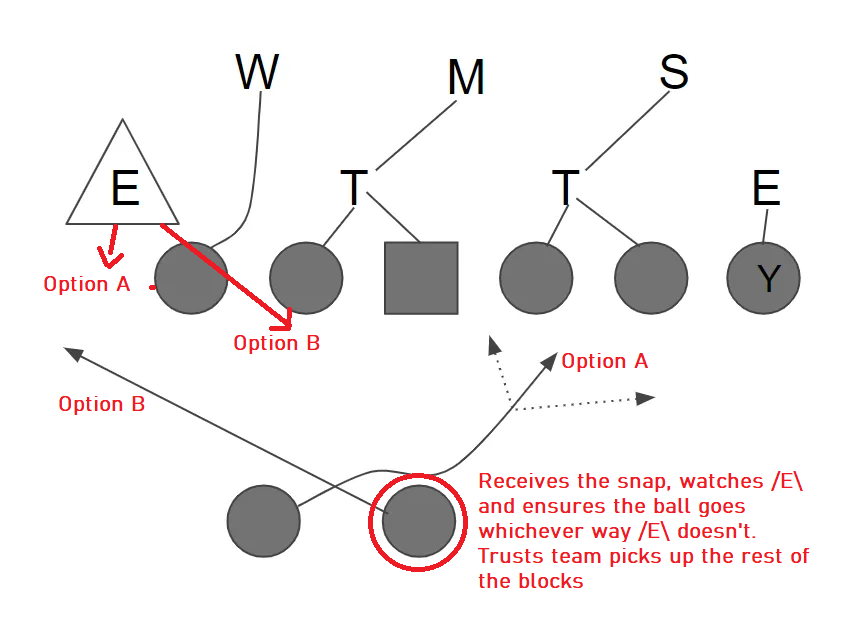

I think what we’ve basically learned from football is that the only sustainable way for a worse team to beat a better team is by using the value of options. Below is a diagram for an offensive football play. The shapes are offensive players and the letters are defensive players. The lines show the blocking assignments of the offensive players. The idea of any running play is the offensive line pushes the defensive players around and creates gaps for one of the two players in the backfield to run through. A worse offensive team who lines up “mano a mano” against a better defensive team will not be able to create these gaps and they will not move the ball upfield (this is what happens when say an any non Southeastern Conference team plays a Southeastern Conference team straight up any time in the last 20 years). But, the play below is special because it’s an option play. It’s a “zone read.”

In a zone read, the offensive line specifically leaves one player unblocked(!) so as to overblock elsewhere. Often time the player that goes unblocked is a player who’s really difficult to block anyways— he’s no match for the offensive lineman in front of him. Instead, the quarterback who receives the ball to start the play will watch this unblocked player because he has an option. If the unblocked players stays wide left, the quarterback can safely choose the option to hand the ball off to the running back headed to the right. The idea is that while the offensive line isn’t as big or strong as the defensive line, by having an extra blocker (they left the one guy unblocked remember), they can create mismatches and stand a fighting chance to create a gap and move the ball upfield. Conversely, if the unblocked player crashes in (after all he’s unblocked) to cut off the running back’s escape, well then the quarterback can fake the handoff and keep the ball, and now he’s free to run to the left where no one is there (or only blocked defenders are there). The offensive team has taken a disadvantage and eliminated it or overcome it by harnessing “option value.” The unblocked defender is forced to make a choice about what to do, and the play is drawn up so that the offense can ensure he always chooses incorrectly (ipso facto?). Importantly, the reason the play works is not just because the quarterback has a choice (I feel like people get this wrong cuz yay! choices!) but instead because of the structure of what has been drawn up in front of him (over-blocking), which has given him basically 2 good choices (1 good play if the end crashes and 1 good play if the end stays), or probably more accurately — given the defensive end 2 bad choices. And of course, good teams can draw up plays like this too which is scary.

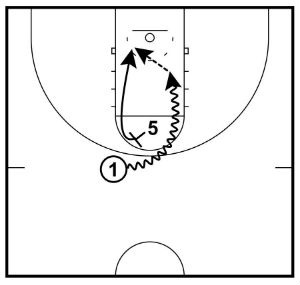

Similar in basketball, there is the pick and roll, which wikipedia describes thusly:

The play (in its elementary form) involves three players. The play begins with a defender guarding a ballhandler. The ballhandler moves toward a teammate, who sets a "screen" (or "pick") by standing in the way of the defender, who is separated from the moving ballhandler. The defender is forced to choose between guarding the ballhandler or the screener. If the defender tries to guard the ballhandler, then the screener can move toward the basket (as the player defending the screener may try to trap or guard the ballhandler, giving the screener space) sometimes by a foot pivot ("roll") and is now open for a pass. If the defender chooses instead to guard the screening teammate, then the ballhandler has an open shot. Alternatively, the ballhandler may pass the ball to an open teammate.

In a way it’s the opposite of the zone read, which explicitly grants the defensive end freedom and thus the burden of choosing what to do. The pick and roll obstructs the ball defender (or threatens to), forcing him into a decision about how to get free (or how to avoid getting blocked to begin with), which the ball handler can option and make the defender more or less always wrong post hoc. Of course defenses can actively try to plan for these options and do weird things to complicate them, but now we’re a couple levels deep into players not just playing on instinct, which is generally a plus for the team who is coordinating as a first order.

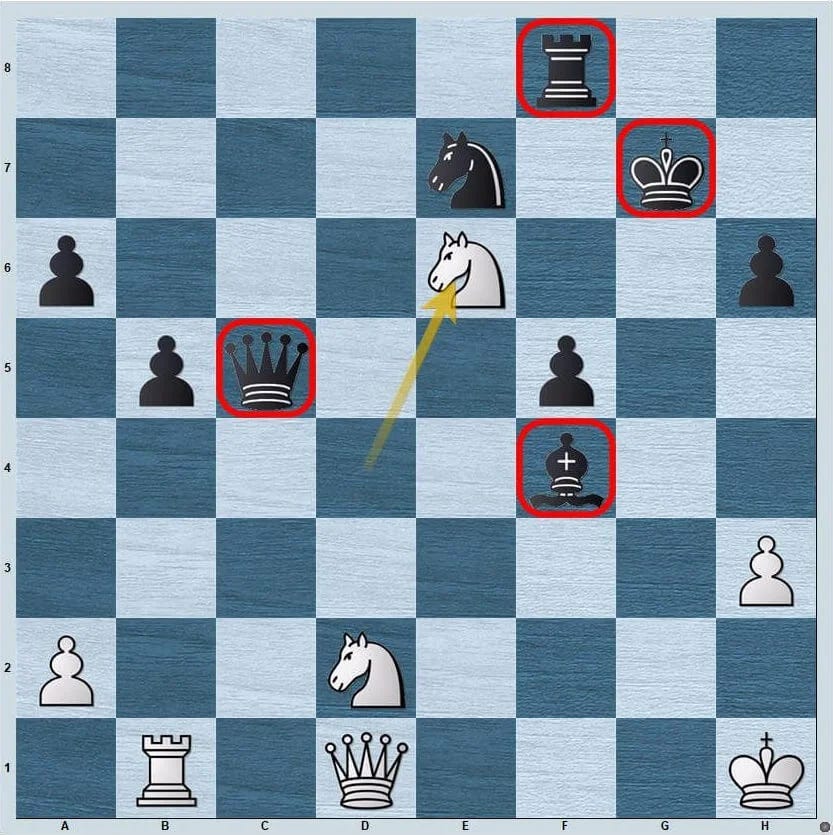

A similar concept to this optionality is just the idea of generating multiple threats for your opponents. This is a big part of chess. Since chess is turn-based and the pieces are the same on both sides, the way to gain ground against your opponent each turn is ideally to do multiple things in one move instead of one.. to generate two threats to your opponent instead of one. Or to both nullify an opponent’s threat and create a threat in the same move. It is difficult to defend two threats at once. Successfully building up your side’s capacity to attack faster than your opponent to the point where you can create two threats they’re forced to address with one single move is often decisive in victory. Think of forks and skewers, but also mating attacks. Up until a final strike, the best chess moves are “principled” rather than “tactical” in the sense that they each suggest a plurality of possible profound threats or concepts. It’s not “what are you going to do about this possible threat” but “I’m slowly working towards a moment when there are too many questions for you to answer and so you have lost.”

I played some tennis growing up, and I’ve always thought of tennis like chess and I’m bad at both for the same reason. Like chess, one side starts with an advantage. The white pieces by having the privilege of moving first begin with an advantage of dictating where the game goes, and in theory each turn they can continue to create threats (or threats of threats) at a constant enough pace and persuasiveness to where the black pieces can never really get out from under the state of addressing threats rather than creating credible ones for their opponent (modern theory between grand masters can often minimize this but it is still not trivial and scary to play with black).

The white pieces start with more options.

Tennis shares this opening advantage. In fact, the server starts with a massive advantage. Even if we set aside that players are bigger and stronger than ever and they can often win immediate points on their serve, almost any serve is dangerous enough for the returner such that the server gets to dictate what the opening threat will be. He starts with options (wide, up the T, into the body). It’s notable that the servers win probability during a point is sharpest right here at the beginning with the returner faced with a spread of very persuasive threats, not wholly equipped to address them all right this minute. Like a goalkeeper facing a penalty kick, the presence of more than one serious threat is a direct factor in the win probability of the point (or the goal scoring probability of the kick taker where he can essentially force the keeper to be incorrect).

For decades, most servers would strive to maintain this opening advantage through forcing play (another chess analog). They would rush the net to cut off the angles their opponents have to return (limit their options), hoping their opponents continue to have only poor options for the duration of the point, hoping that the points end before these win probabilities equalize (before the black pieces can mitigate white’s advantage). Tennis differs from chess in that a tennis player’s optionality really only grows in an outsized way within this one register: space (well, also time — funny how these are always linked). In the modern game (if you set aside the opening serve and say the returner has largely equalized), and you talk about these more common longer rallies between superhuman athletes who can get to the far reaching corners of the court while maintaining depth in the shots they return back, the win probabilities during a point only really start to move again when the space starts to open up for one of the players. A short ball hit by one player means the other player can step in and cut down on the time his opponent has to cover the remaining space.

Now, tennis lacks the important variable that chess and soccer have which is the other pieces in relation to this space-time thing, and I’m veering off course, so.. back to soccer.

The point I want to make in soccer is that as discussed many a time, the basic element of goal probability is time/space, which on its own is a basic version of optionality for a player with the ball. Think tennis or a penalty kick. But because most of soccer is open play and both teams get the 10 outfielders and 1 keeper and the other team is trying to stop you, the way to gain goal probability by gaining space/time is to manage to create multiple threats and force your opponent to choose one. Imagine there’s a defensive end there that has been forced to make a decision and you can make him wrong every time. Or imagine there’s a ball defender in a pick and roll, and you can make sure to gain a half step on him by forcing him to choose to focus his defending a certain way. Critically, the way to create optionality in soccer is through off-ball movement just as the way to create optionality in a zone-read play is based on what your off-ball blockers are doing. The zone-read option doesn’t work if you haven’t created additional threat elsewhere. Too often in soccer analysis, we get hung up on the on-ball decision making (something that is not unimportant), but we don’t focus enough on a team’s ability to create those options with off-ball movement. We scream in agony at a player’s decision to pass or shoot, but we don’t often enough critique why there weren’t more better options available to him.

Take the very analytics-adored “cutback” chance. For some time now, it has been relatively in vogue amongst the soccer analytics crowd (and tactics nerds too) to recognize the relative poverty of traditional crosses from the corner of the box, lofted hoping to find the head of an attacker in the box and conversely to praise the “cut-back” chance — a cross, sure, but a sort of super-powered cross. Whereby a player plays the ball along the ground back across the face of goal to a trailing runner in the box. See the hilariously-scaled google-image find below:

Most importantly for today, while these cut-back chances are good because they’re footed shots from the ground instead of headed shots off floated crosses, and while they’re good because often the outfield defenders’ bodies are turned toward their own goal (the sort of parameters you might include in an xG model measuring the value of the shot at the end of a cut-back sequence), cut-backs are foundationally good not because of that stuff but because they create multiple compelling threats that the goalkeeper has to choose between. Because the ball carrier has entered the box, if the keeper dos not guard the near post, he has a problem since the shortest distance to the goal is to shoot at the near post and the ball-carrier can just do this. If he does guard the near post, then he has a problem because any successful pass now is a clear cut chance against a fairly open goal (think PK but not that good). And so the important take away is not analytically to choose to take cut-back chances instead of floated crossy header chances it’s to figure out a way to create that option scenario to begin with. Figure out a way to create multiple threats so that the defence ultimately must choose and then by definition be incorrect post hoc. How do you create this cutback optionality scenario to begin with? Honestly, it probably is the result of some other option scenario further back in the possession chain. Soccer’s weird, so sometimes you just end up with the ball in the box off a fluke (seriously), or you end up there because you won the ball back in your opponent’s third, but for our purposes if we’re talking about buildup or some kind of intentional attacking play, the way to have ended up in this bountiful option scenario is to have previously created multiple threats and then have had the defense choose which to focus on. Very commonly a sort of 2v1 where the defense will repeatedly choose whatever the most central threat is to focus on, thus opening up a slightly wider progressive pass to a player in the wide areas of the box.

So yea, I don’t know, file this one in the growing bin of “off ball movement matters” posts. Maybe there’s a way to remember to use this framework though when evaluating players, tactics, game models etc. Ask the question how is it that we think we’re creating an advantage and then question it if it doesn’t somehow involve this “multiple threats” / “optionality” stuff in there somewhere. OK gotta go.

Just came across your Stack - very interesting heuristic in this article. I think about these issues a bit differently and anchored more in investment analytics than corporate finance. What you label as 'optionality' is to me comparable to decision/performance attribution, both on and off ball.

That is discrete from the other aspect you reference which is spatial vs time dynamics. Those are more aligned with whether a system is urgodic or not, and has material implications on modeling choices and related inferences, IMO, when trying to analyse performance over time and using to try and forecast into the future.

good stuff, absolutely believe that "options have value." I coached soccer for almost 15 years, and if you can get your players to show up in different attacking positions, it's really hard to defend.