I think it goes like this.

So you’ve got a team with $200M worth of player wages kicking off against a team with $20M in player wages, something that happens regularly in the Premier League (that’s the equivalent of say Man City and Bournemouth). Teams with different orders of magnitude of overall player talent (if we’re to trust the market to some degree…).

Let’s accept the findings we’ve learned over the last decade that in general, a team’s (or player’s) ability to convert shots into goals regresses over time to the underlying pre-shot probability of the shots they attempt as modelled based on the usual xG stuff like where they’re taking the shot from, with what body part and some other context. In the long run a team is generally as good as the chances it creates relative to those it concedes. And in the short term, you just flip a coin, or roll some dice. So that means that when .. hell Man City and Bournemouth play, there’s this underlying measure of their performance that we would be interested in that is unaffected by the short-term variance of shot conversion in the match. We might even say there’s the underlying performance of the teams on the one hand, and a series of dice rolls on the other, which are attached to the shots each team creates and govern their conversion into goals. Somewhere in the maelstrom of shot conversion rates, there is also the individual finishing skill of those taking the shots, but it’s impact is just a drop in the bucket compared to the pure variance between whether a shot goes in and it’s underlying goal probability. We will ignore it today.

So before the game kicks off, it has to be said, we’re expecting Man City to win the match because their team is 10x more talented.

If you’re a Man City fan and you believe that, and you believe -again- that in general a team’s ability to convert shots into goals regresses over time to the underlying pre-shot probability of the shots they attempt, and you believe that a single soccer game is not enough time (not enough shots) for those conversion percentages to regress reliably to their means, then you’re scared of variance. If you’re scared of anything as the $200M Goliath facing a $20M David, you’re scared of those dice that are going to be rolled. If you could take all the dice away and just let the game be decided based on whose players are better you would.

So it goes without saying, but you really do not want each team to end up with a handful of similar shots — or expected goals figures in this match.. That would be a disaster. And anyway, a team that’s 10x as talented shouldn’t end the match with similar shot figures (or xG). Further, it would be doubly catastrophic, because achieving equal chance creation doesn’t even ensure the match ends in a draw because we have to flip a bunch of coins now, or roll a bunch of dice and Bournemouth could just as easily win. In a roll of dice. it doesn’t matter how talented you are. And so you really don’t want it to even be close. And unfortunately most soccer games will be close enough in terms of underlying performance that these dice rolls really matter — this is actually what makes a soccer match like this worth watching.

But we skipped a bunch of stuff that exists. Of course there’s the part of soccer that’s not just rolling a die to determine whether a shot goes in. There’s this other part where the players are all trying to execute tasks individually and collectively. There’s intentions and real causation. There’s skill and ability and endurance. And yet, all of that rests upon or is contingent upon some other dice rolls we have to discuss.

Types of Dice Rolls

As I see it, there are dice rolls to

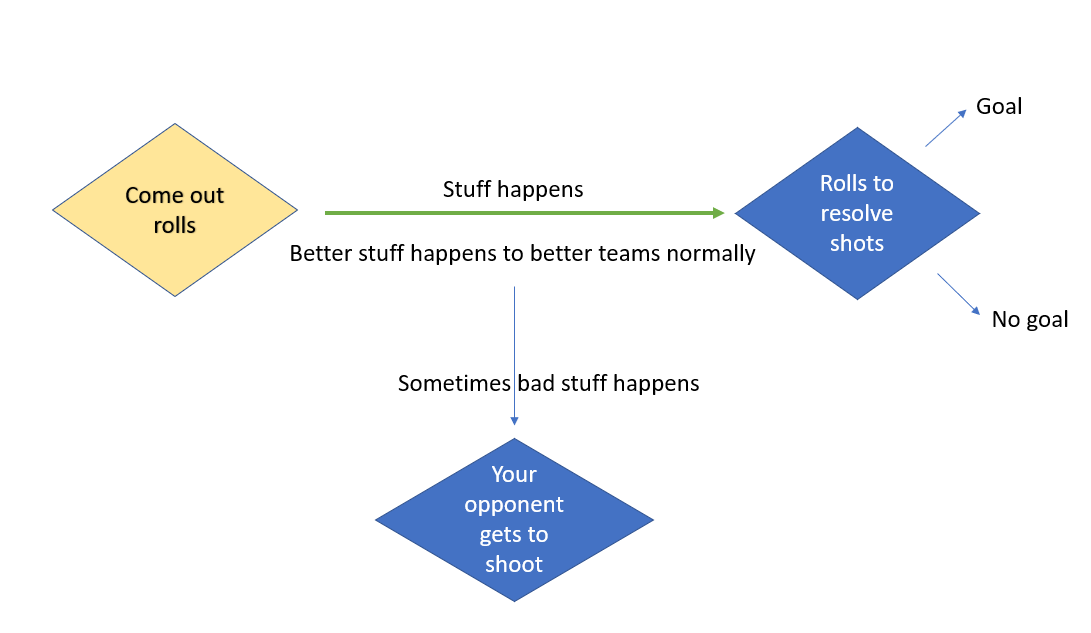

1) “start things happening” or more accurately to “see if things might now happen” - I wanna call this the Come Out, and then there are dice rolls to

2) “resolve things that are in the process of happening” (the big one is shot conversion, which we’ve already covered but there are others). And maybe there are intermediate rolls that partly determine for any given action that’s taken place what the next action’s going to be. The players have agency on the field, but they don’t monopolize it. There remains randomness always.

A good on-ball mental image of a “come out” dice roll might be a risky forward pass through traffic, or a 1v1 take-on. A good off-ball mental image of a “come out” dice roll might be, the aggressive positioning of off ball players for the purpose of stretching the defense and progressing the ball but at the expense of the attacking team’s rest defense (transition-defense-ready-shape). But you might also imagine the defense rolling the dice by setting their line of confrontation high up in the attacking half (baiting a team to play through it and give up structure/positioning in exchange), or to push their backline high up toward midfield (baiting a team to play over the top at the risk of not bringing the attacking structure forward in an organized way). I think it’s useful to imagine all of these as dice rolls in a way (strangely), because each one involves a team accepting risk and inviting their opponent to attempt to accept an opposite symmetrical risk. Each example, of which these are just a few, involves an openness to things happening, whether they be good or bad for the teams involved. And it should be said, teams can (and do) refuse to pick up the dice and roll them. Quite often they do not want things to happen. Things happening can be scary.

Tactics

Where this post is headed is that if you’re the ‘better’ team, there’s a strong emotional(?) bias towards taking the dice rolls out of the game entirely with controlled buildup. After all, it’s this randomness to begin with that creates the opportunity for your lesser opponent to get one over on you. Why don’t we just eliminate the randomness. Ah, but see… soccer is a paradox of sorts. To decrease the random chance that your worse opponent defeats you, or draws you, what you really need to do is increase the amount of soccer that happens, increase the number of times you start things happening. And I’m not sure everyone gets this, just yet.

You may think to control the game and eliminate randomness you want to put your stamp on the game, defend by keeping the ball away from the other team, strangle the game away with possession. But if you don’t roll the dice on the “come out” the game never really gets going. Yea, you can maybe mitigate the dice rolls that resolve the things that have happened (so as to avoid downside risk), but you do so by decreasing the chance of things happening in the first place by trying to control ‘play.’ You try to limit the number of “come out” roles the other team gets by limiting your own. Sure, it’s possible to do this — to dissect your opponent because you’re 10x as talented as they are. You choose the safe pass time and time again in buildup, hoping to tire them out and eventually break into the penalty area. But more than likely this more controlled buildup — a hesitation to roll the dice on the come out — will just mean that less stuff happens in general during the game. And if less stuff happens in general during the game, then there’s a real chance you won’t win! Because if less stuff happens in the game, those second dice rolls — the ones that resolve how the stuff that did manage to happen gets accounted for on the scoreboard (shot conversion) become even more important. By limiting the number of “come out” roles in your game, you might end up with 5 shots (subject to 5 dice rolls), and maybe your much weaker opponent has 1 or 2. This seems bad to me if you’re the stronger team.

If you’re the stronger team, don’t you want more stuff to happen because it gives you more opportunities to beat your opponent at the stuff you’re better than them at?

In order to actually let the game happen, which is something you want cuz you have the better players if you’re Man City, you need to roll the dice on the “come out.” You want to let the game breathe and to have the ball move back and forth a little, which might mean losing possession some. Let both teams try to start things happening, confident that if they do that, there will be more space for everyone, and you’ll have more dice to roll for goal conversion (because your team has the better players operating in all this space). If Bournemouth have to actually play with the ball and move players forward, there’s a strong chance your defenders who are maybe 10x better than their attackers will not be troubled. And there’s a chance that your attackers who are maybe 10x better than their defenders will feast as the game opens up.

So far we’re talking about the game pretty abstractly right? (sorry we’re gonna keep doing that - it has a purpose). But we’ve been talking about the game as sort of agnostic of specific tactics or even the idea that there’s some specific factor into the success of things that’s based on how well a team is drilled, how clear the game model is to the players, and how appropriate it is relative to the opponents strengths and weaknesses. So far we haven’t considered those types of things (coach influenced things) in our analysis aside from some overall risk appetite of “willing to roll dice on the come out” or “not willing to roll dice on the come out” — that is to say some tolerance for the amount of soccer that’s going to be played (as manifest in some sort of vague idea of how you control the ball in possession).

But let’s add in that there’s also some concept of “yes Man City has the players who are 10x more talented than their opponents, but we’ll pretend that Bournemouth’s coach is so good that he’s able to do more with less. He’s got them so drilled on the game model, or he has such unique, clever ideas about the game, which he’s instilled into the team, that he’s able to punch above his weight here in terms of the team’s performances. This less talented team has more of a fighting chance (other than through those dice rolls we talked about) because of how he sets them up.” Let’s add in that concept which I put in quotation marks for some reason. Basically, we have to add in the concept that a coach can change not only the amount of total dice rolls but the allocation of those across both teams. And the reason we have to do this, is that the stakes of figuring out this question are pretty big.

You can see every week in the media how quickly we attribute success or failure to a manager irrespective of the level of talent on his team relative to his opponents, and irrespective of whether the coins came up heads or tails. Everyone wants to praise or blame the daddy. The media basically thinks that this coaching feature (the ability to shift the balance of dice rolls towards your team’s favor via tactics or even man-management) is the defining attribute of a coach, and the factor that bests all these other factors (the outcomes of the dice rolls, the differences in player quality, etc). The media seems to anchor narratives on this idea of the coach as tactics picker.

But you’ll then hear from us nerds how in general, coaches don’t really matter. That in the end, it’s just the quality of the players that determines the results over time. Is this true? And if it’s true, why might that be (if this other coaching stuff exists). That’s really the point of this post. Exploring a reason why it might be true that the lion’s share of a team’s performance is down to the talent level of the players, while also thinking about this high level choice a manager has around risk appetite, and then this other thing where maybe he’s a better tactician or man-manager.

The real question is like, what is the ordering of significance of these various factors and dice rolls, and then is there something going on that makes this “manager doesn’t matter” finding largely stick in the long term?

OK, so maybe we have this framework:

FRAMEWORK

Output:

The number of “Big Dice Rolls” for both teams, the outcomes of which determine whether shots become goals (and therefore whether teams get wins, losses, or draws, and whether or not fans want to fire the manager)

Inputs:

How many big dice rolls each team gets to roll and/or how many sides of the dice there are is largely determined by the following inputs:

Individual player quality, and specifically the difference between how good players on one team are vs the players on the other team

How much game is allowed to happen, such that the differences in player quality from #1 has room to show itself, to impact what happens out there. Using my analogy above, I equate this to how many come-out rolls there are in a game), how many times is a team able to roll a dice and take a risk in buildup or in attack/defense so as to find the space to show its quality. This is in part determined by:

The risk appetite of each team. It takes two to tango.

If neither team wants to accept risk, not much game happens at all. Maybe one team controls the ball and the other team compactly defends, or in probably less common cases, neither team controls the ball and they just lump it back and forth with a runner or two. In these matchups, there are very few “come-out rolls.”

If one team wants to accept risk, but the other team does not, then we enter a second cycle, whereby the team that wants to take risks is basically baiting the other team into attempting to punish said risks (so as to then be able to roll the dice upon the opponent opening up), otherwise you kinda just end up in that first scenario.

In theory, these are the “tactical” decisions each team makes that are most impactful on the results of the game. Basically, whether the two teams will conspire to allow very little game to happen or a whole lot of game.

If we know how much of a difference in quality there is, and then “how much game” will happen, we are most of the way there. But there still remain a few modifiers that we know can impact how many Big Dice Rolls each team will get. These are:

Home Field Advantage — we know that teams that play at home are able to create more chances than when they’re playing away. We don’t know why this is exactly, but you can imagine that similar to #5 below, if a whole team worth of players can achieve some modestly higher “flow state” or “on-the-same- pagedness” because of their familiarity with the sight lines, or the extra rest at home they got, or the sameness of their home routines, or perhaps some psychosomatic bonus from “defending their home turf,” then it would show up in the aggregate home/away performance spreads, and it does.

Togetherness Bonus — similar to the above, if one team trains significantly better than average, or bonds significantly better than average such that the players are able to achieve some modestly higher “flow state” or “on-the-same-pagedness” you can imagine how that might manifest itself in their ability to create good outcomes (e.g. Big Dice Rolls) at rates that exceed some kind of benchmark rate.

Tactical Bonus — if one team “figures out” the other team, such that their tactical approach is the antidote for the other team’s poison, you can imagine how this would manifest itself in an improvement in that team’s outcomes (e.g. Big Dice Rolls) at rates that exceed some kind of benchmark rate. This would is possible, but I’m not putting it at the very bottom of this framework by mistake. It seems very much secondary to all of the above more repetitive, substantive factors. Tactical approaches that are not specifically turning the risk meter to the right or left very much have to “get in line” behind all these other inputs.

Other small dice rolls — you know… bounce, chance. These small dice rolls happen literally every possession, several times per possession probably. Whether a pass takes a weird hop, whether a ball played across the box, skips just past a runner, or over his foot, or whether it falls perfectly such that he can get a toe on it. Whether a contested take-on ends with the ball falling cleanly for one player, or another, or something messier. Whether a no-look pass lands perfectly for the receiving player, or whether the idea was correct but the very difficult pass idea could not be completed this one time (since every pass attempt has some kind of innate probability attached to it). There are a myriad of weird small dice rolls that happen throughout a soccer match (minor referee decisions). My hunch is that most of the time, there are enough of these little dice rolls that they basically even out across both teams, or they don’t even out but their significance on match outcomes is very muted based on where on the field most of them happen.

Practical Uses of this Framework

Among its many uses, holding this framework in our heads when we think about tactics and managers puts their responsibilities into perspective. I think too often we think about a manager as being the single throat to choke, fully and entirely responsible for the outcomes of his team’s matches. We might then slip up and assume that the outcomes of matches are primarily the result of manager decisions or some other manager quality. If you sit with this framework for a second, it becomes clear that while the manager does implement a game model, and yes he has a big hand in determining how the team goes about playing in matches (he runs training after all), perhaps his most influential decisions are more around how much he wants his team to cooperate with the other team in allowing for the teams to take risks and let things happen. Put entirely too bluntly, the first tactical choice is “how much stuff do we want to allow to happen in this match” And if results are paramount, it should be pretty clear that vastly outmatched teams should choose “as little stuff as possible” and overly powerful teams should choose “as much stuff as possible.” Once you imagine a match as firstly a conflict between two teams of varying strengths/abilities, and secondly a conflict around how much soccer each team wants to play, inversely related to how good they are, there’s just not a ton of room left for all the other factors, that we more intuitively imagine as being what we decides matches, or the stuff managers should be fired or hired for.

Further, while it feels awfully heretical, it seems to me that a really detailed, strict, explicit game model might to an extent get in the way of a manager/team having the ability to flex this really important consideration of “the amount of soccer that they want to have happen in a game.” Perhaps for the best and worst teams, this flexibility isn’t as important (although it becomes tricky when they play their closest peers), all the teams in the middle of the table should really make sure they can flex up and down on this scale of rolling the “come out” dice or allowing their opponents to. That said, if I had vastly the better players than any other team in the league, I almost… wouldn’t want my the manager getting too involved in the actual tactics, for fear of this intervention interrupting the otherwise natural advantage the players have. I would want the tactical instructions to be most focused on opening the game up and creating a fertile ground for “things that happen,” tactics for baiting my opponents into playing, rather than focusing on absolute control over a quiet game.

For teams at the bottom of the table, the most important tactical consideration isn’t how the manager sees the game, or a dedicated game model that he can grow at the club and excite the fans. He needs to be able to manage most matches in such a way that the opportunities (time) for better players on the other teams to make things happen are minimized. His job is in a way, to prevent soccer. And then he needs to get incredibly nuanced and tactical in the matches where his team is evenly matched with its opponents, deciding when to open up and accept risk in order to reach for a six pointer, and when the table math and the larger season context demands conservatism even when facing a team of relatively similar quality. This sort of concept would explain perhaps why someone like Sam Allardyce was able to make himself such a hot commodity for teams facing relegation. Part of this is incredibly obvious, but I think it’s somewhat illuminating for us to think about what not to focus on when it comes to managers — again if results are paramount. You could convince me it’s not all about results, but sooner or later, results come for us all.

Applications for Analytics: Past and Future

So first, just a reflection on like… the whole players vs manager debate. The old Soccernomics finding was that y’know like “most of the variation in league performance can be explained by wage spending.” I have always enjoyed that this is one of the ancient soccer analytics findings that predates much of the online blogged soccer analytics canon (see the Post Script podcast where John and I are slowly making our way through the early online analytics body of work). To me, it’s incredibly appropriate that that it’s one of the early contributions, because it’s a context that really can’t be ignored when we ask all of the other soccer analytics questions that we ask. And we often do ignore it because this particular wage data is hard to come by. But I’ve long been curious as to the “why” and “how” questions — as one does — and as it relates to this topic, something like:

Deep down, I think we know that managers “matter” in some absolute way, but if that’s true, then how do we end up with this Soccernomics finding? Or put another way, if we accept that the players are what matters the most, but also we think that what managers do does have an impact on the pitch, why is it only the player-ability centered data that seems persistent and all the other stuff ephemeral in the long run.

And I think that framework above (if you scroll up) does something to answer that question. It’s kind of just that the major impacts a manager can have are to emphasize or simply minimize the gaps in player quality rather than to shift the balance of which team is “better.” There are all these different things managers do, and all these different decisions they have to make, but the most impactful ones they make are obvious and counteracting, and only serve to speed up or slow down the bigger factor of player ability. The best managers squeeze a few more dice rolls out of a good team they’re managing and prevent a few more dice rolls when they’re managing a bad team. And that kind of impact just can’t really hold a candle to the persistent difference in player quality. And even when managers are able to “shift their team’s big dice rolls to the right” so to speak, these effects are battling not only player quality gaps but also home field advantage and other stuff.

There’s a hurricane of other effects, random or otherwise, and so all these marginal advantages are just hard to pick up (relative to other sports). The one advantage that is most stratified, the most significant, the most persistent is the inequality of team rosters at the highest level of football.

Because of that, this post… basically doesn’t apply to MLS, due to the enforced levels of relative parity inherent in the league’s bylaws and labor agreements etc etc. I’m sure there’s something we can take from this for MLS. Or if you’re going to apply this framework to MLS, you won’t necessarily end up at “in the long run, the players decide the games.” You might, but you might also land at “Major League Dice Rolls” as someone recently put it on twitter. [post publish edit: OK I’ve had some folks ask me about this comment, if I really don’t think the framework applies to MLS. It’s not that it don’t think it applies. I still think the factors in that framework work that way. It’s just that, once you shrink the player quality gap, the factor that serves mostly as an amplifier (or the opposite) for that quality gap, and the thing that the post is most interested in exploring (the come out rolls) just becomes less of a factor — the same way that the other factors that weren’t piggybacking on that big player quality factor were largely sidelined in a league with large player quality gaps. So if anything, yes you should use the same framework for MLS and but use these same lines of thought to maybe come up with answers that don’t call for a whole lot of specific action?]

In terms of future work, I guess I’m kinda? excited at the idea that this high level tactical choice of “more vs less soccer” could be measured in some way, and then once it is measured, we could use it to determine which managers are getting this strange first question correct more often than not. And then, we might also use this measure to put a finer point on the original players vs managers finding, and the ongoing debate. Lastly, I think frameworks like this are always just helpful to sit beneath whatever analytics question of the day we’re trying to ask.

PS: If you haven’t read Ryan O’Hanlon’s book “Net Gains,” you should check it out. I feel like he never loses sight of the interaction between money (and therefore player quality disparities across teams) and soccer data findings.

Perhaps most specifically, soccer analytics has wrestled often with what is the correct denominator to measure player metrics against. Raw totals have their problems. Should we adjust for games played, or is it minutes played? Say per 90 minutes? Should it be per 100 possessions, or per pass? And then how should we adjust these metrics based on team effects and how often a team has the ball and on and on… And I think this framework would propose we should probably be adjusting our cumulative stats taking into consideration this concept of a team’s risk appetite. Some way to adjust minutes or possessions up or down to reflect when teams are “rolling the dice” and going for it, taking on risk etc, and when they aren’t. A small step towards “adjusting for tactical context perhaps?” Since what I’m suggesting is that the primary tactical impact is one of risk appetite, it seems like reachable fruit. And this should interact with game states in intuitive ways too. After all, that’s one of the main differences between different combinations of score lines/minutes remaining in matches: the risk appetites of one or both teams. And as some of the most thoughtful game state literature has considered, even at minute zero with the game level, a week team might act more like a team protecting a lead in the 85th. These things are related: team strength gaps and how teams act while leading as minutes expire, so instead of trying to adjust for game state using these what I might call “output measures” like score line and minutes remaining (and risk over-fitting models etc), it would be nice to be able to use a catch-all “input” measure that is trying to directly measure what the teams are actually experiencing out there, something that represents their behavior (I don’t feel certain about this but I’m reminded of how early xG modellers had a dilemma of whether to shove the scoreline into the model to capture the additional conversion probability a team experiences when they are leading or modelling directly the context that makes the probability higher, namely the presence of a counter attack which typically faces fewer defenders etc).

Anyhow, someone who’s actually good at this stuff should give it a go.

Oh, and don’t talk about this to players. Intuitively they get all this more than anyone. You don’t need to explain it to them. And they don’t need this up there competing for their concentration.

Brilliant as ever. I hope someone indeed tries to apply this framework. It might be helpful to describe what a “soccer stuff” action might be. Certainly a through ball. But a cross? Any pass from outside the box into the box? A “direct” long ball that breaks the final third? Be curious your thoughts.

On managing - two things. It seems to me the goal of Pep and his Arteta tree is to take risks while minimizing the opportunity given the opponent for taking said risk, through the acute management of player positioning. Certainly the manager can impact the game here more so than the sheer volume of stuff. Second, I think it’s understood that money buys you into the title race. But can’t we give a decent amount of that marginal credit to a manager based on whether or not said team manages 5th, 3rd or 1st? Aren’t we all judging Klopp, Pep, Arteta, etc not on whether or not they compete for a trophy but whether or not they provide that extra bit of stuff that gets the team those extra rolls of the dice?

Your comment on mid table teams being able to play up or down within a risk context was very interesting to me. As a wolves fan I feel like this applies to what I like so much of our team. We have multiple players in multiple positions that can scale up or down, if you want a manic dribbler to scale up go bellegarde or a safer level headed passer go sarabia, you can have the dogs of war in midfield of lemina/gomes increasing risk with pressing but decreasing with passing or tommy Doyle who will do the opposite. What I like about O'Neil is I think he understands that and he knows when to increase or decrease football shenanigans but more importantly he has the players on the pitch to do it.