Theory of Transfer Fees

Slouching with mixed success toward a semi-coherent framework

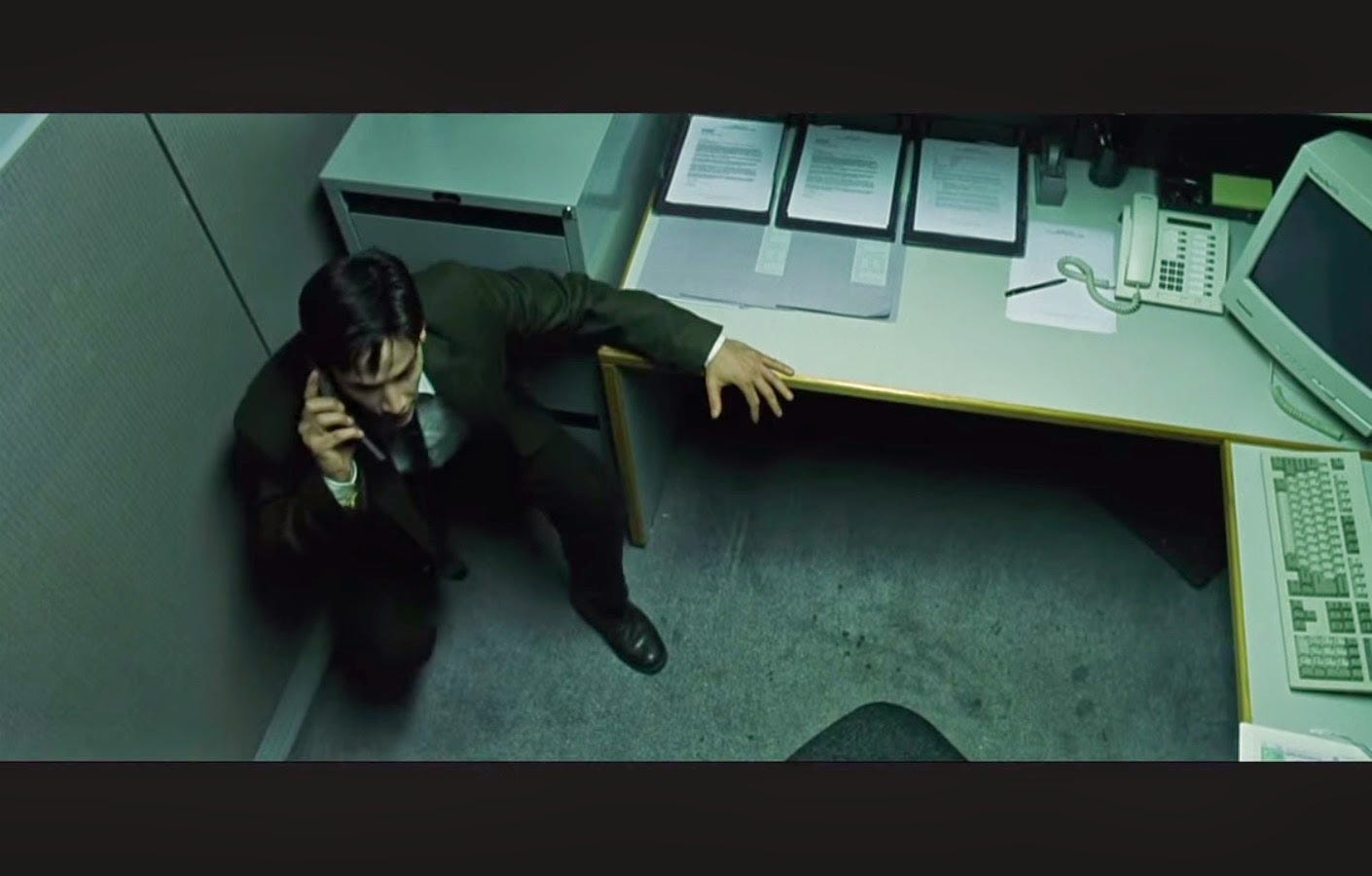

After the last post detoured into a meditation on the nature of soccer, measurement and what comes after, I would love to return to the “core” Absolute Unit cycle, where we were using a corporate finance analogy to explore a theoretically sound player recruitment process in a front office. As I recall, we had projected a given player’s contributions to team goal difference mimicking the way a valuation analyst would go about valuing a company in the business world, starting with historical accounting records (soccer data), adding in the unit of account, and then making pro-forma adjustments and applying other factors to take into account realities we understand about the sport. Certain regrettable PowerPoint graphics were involved:

Next we would need not only to project the player’s contribution to team goal difference, but benchmark these projections against other available players (on the transfer market or from within an academy).

And I definitely want to get back to benchmarking at some point, but for today, we’re going to jump forward to chatting about transfers. Just seems like we need to firm up our understanding of where this whole projection process eventually goes in the recruitment cycle to help us work through the rest. And with the primary transfer market window in many major leagues having recently closed (and with a bang), it’s a good opportunity to talk about “value” and “transfer value” and ‘transfer fees” and “transfer markets” and “transfermarkts(?)”

Player contracts as inputs into a production process

Soccer players sign multi-year employment agreements with soccer clubs (or with leagues in the case of MLS), promising their services in exchange for wages and other benefits. The primary benefit a club enjoys from the player’s services is his competitive value, measured in its raw form in terms of marginal goal difference contribution (“goal contribution”), whereby a player’s inclusion in the team through his on-ball (and off ball!) presence changes the probabilities of a team scoring (and conceding) over some time horizon. We suggest here that this change in goal scoring probabilities brought about by “things that happen in soccer” is the best “unit of account” from which to organize front office operations.

A soccer club takes a player’s goal contributions and combines it with other goal contributions (other players, coaching staff, physios, nutritionists, sports psychologists, analysts, etc) to produce a competitive product on the field (which can largely be measured in goal difference). Then, it combines this “competitive product” with non-goal-denominated contributions from the back-office and other departments in the organization (investments of time, energy, creativity, and not-trivially, money) to market the club and attract spectators on matchdays both in the stadium and on television to generate revenues (and other less significant incomes).

As John Muller suggested to me, trying hard to hide his disgust at how many words I had typed to say the same thing: “Clubs make money by winning.”

So anyway, a club and a player enter into a labor contract which binds both parties into satisfying the promises they make to one another in the contract and all else equal, it will continue to do so until the earlier of 1) its specified term ends or 2) all of the parties agree to otherwise terminate it, amend it, assign it etc.

Why terminate a contract?

There are a few reasons why one party (but not both) would want out of a labor contract. These include but are not limited to the following poles:

The player might be performing at a level so low that the club regrets paying him as much as it does, and it would love to stop doing so, so that it can divert those wage funds to some other player that will produce at the desired level. Naturally, a player is typically happy to continue in a contract like this — he’s getting a decent deal here — and in no rush to solve the club’s problem by voluntarily terminating his employment. The Liverpool fan in me remembers several years of the Reds trying to offload Joe Cole’s contract.

Alternatively (and more prominently in the news), the player might be performing at a level so high that he believes he should be getting paid more. If he could only terminate this contract, he could enter into a new contract at this club or with some other club where he would continue to provide soccer services but be paid more. Conversely, a club is naturally in no rush to terminate these types of contracts. They are delighted to be receiving high end performance at a lower fixed cost. It’s a sweet deal, and they’ll always say something like “well, contracts exist for a reason,” at least at first.

Both of these contractual situations exist everywhere, and in all of these situations, the existing contract will remain in force and the player employed unless… something comes around to convince both parties to legally terminate the arrangement.

While I suspect the former situation is one of the single biggest and most common headaches a sporting director navigates on a day to day basis, it’s the latter situation that sells newspapers and draws clicks. In this situation, for an overperforming player’s contract to be mutually terminated, the player needs assurance that his next contract is going to net him a handsome pay raise (another club needs to offer him a bigger deal), and his current club needs… to be convinced somehow to allow this.

Transfer fees as contract termination fees

If a club is enjoying a level of incremental competitive return produced by a player under contract which exceeds the equivalent wage rate he’s locked in for, that probably also means that they expect this phenomenon to continue over the remaining term of the contract, and they’re thrilled about this. After all, winning costs money, and they make money by winning. This “good” contract is making them money in the sense that if they were to win at the same rate but with a different player, they might well have to pay more than what they’re paying now.

We know the academic financial framework from previous posts that if you want a stream of excess financial returns over and above what the rest of the market is offering, it’s possible to acquire it. You just have to pay a higher price for it, and by paying that higher price upfront you bring the overall expected return back in line with the market return! Offering a club a transfer fee in exchange for them giving up a projected excess return over the remaining contract term might just do the trick. Basically it is this number offered to the club, along with the improved player contract offered to the player, which together bring about the termination of the remaining player contract. The greater the remaining excess returns the club projects over the remaining contract term, the higher the transfer fee will need to be at a minimum to convince them to terminate the agreement. This means that if a player is overperforming, both the extent of his overperformance and the remaining contract term influence the total transfer fee required to convince the club to terminate (no transfer fee at all will be paid for a player with no remaining contract term - a free agent or Bosman). Importantly in almost all leagues, the “buying” club does not get to “buy” the contract (and contracts aren’t “traded” like they are in the NBA, NFL, MLB). Because a “buying club” has to negotiate their own contract with the player, the perfect finance analogy I teased above doesn’t really hold true. They can’t just “buy the excess financial returns and in doing so, bring those returns down to market rates.” They’re just paying someone else to terminate the existing agreement. They’re making them whole for the excess financial returns to be lost, but by now paying a higher rate to the player, they’re not gaining these excess returns dollar for dollar.

Joe Cole and Lionel Messi

To bribe a club to agree to terminate a “good” contract, you pay them a large enough transfer fee. To sign a player who’s on a “bad” contract, his current club needs absolutely no convincing whatsoever. Instead, it is much more likely the player needs convincing to break his current contract and sign a new one with your club. Hell, if you can convince him to sign a contract with you, his current club might even pay some of his wages. But does that mean the player’s “market value” is zero, or negative?

No. The value of the player is first measured in goal contribution, by how much or how little he will increase or decrease your team’s competitive performance measured in goal difference. The player offers the “competitive value” of his services in exchange for the monetary value of wages. So if you’re going to put a dollar value on a player, it’s really the wages you or another market participant is willing to pay him. It’s not some one-off fee you pay to convince another party to agree to cancel a contract.

It goes without saying that even though Lionel Messi moved from Barcelona to PSG for a transfer fee of zero, Lionel Messi’s “market value” is not zero. His value is better represented by the €71M per year PSG is reportedly paying him to ply his trade in Paris. Lionel Messi’s contract with Barcelona just ran out, and then he and Barcelona couldn’t work out a new one. So, that was that. PSG pays Messi and not Barcelona. There was no transfer fee because a transfer fee isn’t the market value of a player, it’s just the amount you pay a club to convince them to agree to terminate a contract.

Replacing a player

When a club transfers a player out, in theory they have “lost” his production towards team goal difference. The sporting director should consult within his department and re-assess whether at the team level the now weakened roster continues to project towards an aggregate goal difference that aligns with the competitive objectives laid out by the board, or if they need to add a player to the squad from outside to replace the outgoing production. I mention this only to resist the urge to automatically think of the transfer fees just received as immediately being added back into the transfer “war-chest” for immediate use toward a replacement player. The club might well have a replacement player already on the roster, and the team’s projected goal difference might yet still align with their competitive objectives.

Front office theory

So the macro theory of this is that whether consciously or subconsciously, in an organized or haphazard manner, successfully or unsuccessfully, front offices are individually and in the aggregate always:

Setting competitive objectives (e.g. team goal difference)

Authorizing operating budgets that align with these competitive objectives (#1)

Projecting the marginal goal contributions (rates and opportunities) of current and prospective players

Allocating the authorized operating budgets (#2) to current and prospective players and executing on transfer strategies to build a roster that aligns the team’s projected goal difference (sum of #3) with the team’s competitive objectives (#1)

Revising the projected marginal goal contributions (#3) of current and prospective players as time passes, matches are played, and results occur (new information)

Estimating the value of current contracts based on the relationship between actual budget allocations (#4) and the revised projected marginal goal contributions above (#5)

Making adjustments to the roster as marginal goal contribution projections (#5) diverge from organizational competitive goals (#1) by paying transfer fees or receiving transfer fees (or some combination of the two) based on the values estimated above (#6), and re-allocating payroll and transfer costs (#4), so as to realign projected goal difference (#5) with competitive objectives (#1)

That to me is the continuous recruitment cycle. Most of it is straightforward. I think we can all pretty easily internalize how in sports, the future doesn’t always match the past nor does it match projections of the future. So this iterative cycle of continuing to project and revise projections of player performance and then comparing these aggregate revisions at the team level to the organizational objectives to ensure alignment and/or course-correct if necessary— I think that’s all intuitive enough. The universal nature of the “goal” in soccer is what makes it a great element to organize a front office theory around. Whether a header on a goal mouth scramble or a bike from outside the 18, the goal event always changes the scoreboard in a profound way and it changes your likelihood of winning the game in a profound way and these ways are essentially the same. That’s why we suggest organizing all of our player projections, organizational objectives, and individual organizational decisions around goal difference and the incremental or marginal impact to goal difference. This should work everywhere, no matter how big or small your club is, or what country or what time period. People understand goals, and importantly, whether this framework is used explicitly or subconsciously, it’s there always. Making it visible just clarifies your plans and your decision-making.

But there’s another iterative cycle that’s happening all the time — and it’s not measured in the “absolute units” of goal difference. And that’s the iterative cycle of the creation of and destruction of, and authorization of stocks and flows of money (denominated in currencies) between clubs, players, agents, nations, leagues, across borders and within and without the global footballing economy.

Money things

If goals have a sort of universal quality, money by contrast is basically never the same— as counterintuitive as it may sound. Some clubs have lots of it and others very little. Some clubs have lots of debt, some are owned by the supporters, some are publicly traded and registered with regulatory bodies like the SEC, and others have the political backing of local and national governments. Still, others are literally owned and funded by nation states and their treasury departments with the authority to print fiat money. Others clubs are more like operating segments within a single company.

An omniscient soccer god (with perfect data, unlimited tactical acumen and scouting experience) could denominate a player’s value in goals all day long, but ask them to put that into dollars and cents and it’s suddenly messy with so many different factors (and virtually none of them football factors). Importantly, if this soccer god is now authorized to spend a fixed budget on building a roster, then there’s no untangling the things he can value perfectly (soccer) with the things he cannot (money).

So take two clubs who are both trying to sign the same player. They might have a very similar player evaluation process, and by some miracle they might arrive at very similar player performance projections. In this way, they both “value” the player similarly in goal units. The player’s current club might also have a singular view as to his projected remaining performance relative to his remaining wages — and a singular view as to how this translates into the excess wages they would need to pay someone to produce the same performance. But when the two buying clubs go to offer him a competitive wage offer, and offer a transfer fee to his current club (if applicable), their respective authorized budgets might be very different. And then not by coincidence, the amount of authorized budgets they can allocate to the same goal contribution will also be very different.

To further complicate matters, the available budget of a single club at any given time may fluctuate a great deal due to the iterative nature of the roster building process, but also due to the iterative and fluid nature of the economy and the transfer economy as a whole. We can easily recall transfer windows in which it felt almost as if the funds from a record breaking transfer fee were cascading across Europe, showing up all summer long in places where transfer fees seemed way higher than they had once been. In other more recent transfer windows, uncertainty has abounded as to the short-term or medium-term levels of matchday revenues (and with it budgets).

Splitting allocated budget between wages and transfer fee

We know already that if two teams are trying to sign the same player, they’re both having to strike 2 deals each: 1 with the player to convince him to agree to terminate his employment and 1 with the current club to convince them to agree to terminate the player’s employment. The difference is that negotiations around player contract are anchored to an extent in so many ways that negotiations around transfer fees are not.

First, there are thousands and thousands of professional soccer players out there, most with multi-year contracts, and these players are constantly competing against one another and alongside one another, and there is measurable data on these players, whether it be event data, tracking data, video or other qualitative data. And they all have agents and their agents all serve multiple player clients, and the agents know each other mostly and it’s like… it’s an actual market I guess. It’s messy and perhaps not very vanilla, but there’s a big, robust “labor market for footballers.”

Second, because player contracts are typically multi-year agreements, the wages that are set in them persist across different time periods, time periods which as discussed above might fluctuate in any moment within different economic contexts, and so they are anchored to a greater extent in medium-term and long term economic expectations. When the robust labor market described above serves as a reference point for a new contract negotiation, it is doing so with stacks of vintages of medium and long term expectations set in the past and across different economic contexts. And sure, any contract negotiation should consider projections of the future as well.

Conversely, for transfer fees which are not multi-year agreements but mostly just payments between clubs at individual moments in time, there’s not really an equivalent “anchor.” There’s no true “market” to look to, because when a “buying club” pays a “selling club” a transfer fee, they haven’t bought the player. They haven’t even bought the existing player contract (except in MLS). They’ve just bribed two independent parties to terminate a contract they weren’t a party to. There might be a website called transfermarkt listing off estimated “market values” next to each player, but there’s no such thing as a “transfer fee market” to back this up. On my read at least, it is a fiction, even as reports begin to surface of clubs referencing these values.

Transfer fee pricing theory

So then a take-away is that the “pricing model” for transfer fees -if you want to call it that- is first a function of the authorized budgets clubs are willing to allocate to sign a given player (having already valued the player in terms of goal contribution), and then second, this allocation is split between 1) player wages and 2) transfer fee.

Again, the pricing of player wages is anchored much closer in observable market inputs and comps, and then what’s left over flows through the “transfer market” in an admittedly quixotic and contested process between “buyers” and “sellers” where each of these terms is problematic, but where the “sellers” calculate a “floor” below which it is not worth it to them to terminate a player’s contract given his estimated remaining performance relative to his remaining wages (and with some conception of a replacement player’s equivalent wages) and where the “buyers” have already calculated their ceilings — the amounts of authorized budget they’ve allocated to the competitive output of the player remaining after they’ve tentatively agreed a new wage with the target player over the new contract term. This second piece, the pricing of a transfer fee is a contested, murky, and residual affair, secondary to the weight and substance of the pricing of a player’s wages based on his performances, but for some reason (neoliberalism) it grabs all the headlines. Because it’s sort of ephemeral and abstract, the fee can seem exceedingly low or exceedingly high, depending on the moment. Unanchored, it’s just sort of all over the place by identity.

Despite how pundits treat it (always too high), it’s not the price of eggs or sugar or gasoline. It’s a bunch of entities trying to bribe each other to break labor contracts while also tempting players to break those same labor contracts. And there’s another reason these fees can soar, detached from any traditional pricing anchors. There is another source of upward pressure: accounting.

When accounting fails to reflect reality, it still shapes it

Adding further fuel to the transfer fee fire is the fact that from an accounting perspective, transfer fees are counted as income in the year they are received, but transfer fees paid are counted as expense only gradually over the acquired player’s contract term. You could receive a €15M transfer fee from one club for terminating one of your player contracts, and pay €15M to another club to sign a 3 year contract with a new player, and your incremental net income for the period would be a positive €10M (€15M received minus expense of €15M/3 years ). In a typical business, owners and shareholders care (or should care) about the timing of actual cash receipts and payments before they care about the timing of the accounting recognition of profits and losses; however, many of the biggest soccer clubs in the world are governed by and directly impacted by Financial Fair Play regulations or other domestic bylaws which explicitly cap transfer and payroll spending based on a maximum allowed net loss or on other figures like a percentage of topline revenues (the timing of which is governed by accounting rules, and important for our use case, has that particular accounting asymmetry around incoming and outgoing transfer fees). There are also clubs that care more about winning than cashflow.

The infinity of accounting and “Financial Fair Play”

Financial Fair Play (“FFP”) which “governs” roster spend in UEFA basically says that a club can’t spend more than €5M over their revenues over a 3 year period (excluding certain approved capex type costs, stadiums, youth facilities etc), and this number goes up to €30M if your owners are financially well off (for reasons). It occurs to me, and perhaps I’m wrong, but there’s a certain transfer budget multiplier at work here.

Imagine that UEFA comprised only 10 wealthy clubs (lol, this isn’t starting off well), and they each generated €300M of revenue, €180M of payroll cost, and €95M of other operating expenses (excluding transfer fees paid). Add €15M in interest payments and €20M in taxes, and each club is operating at a €10M loss annually, which complies with the €30M loss over a 3 year lookback period under FFP. If each team (all of them, this is a closed model) wants to make a roster change and sign a player who’s out of contract, or finds a player that another team is willing to let walk for free (and the player wants to), then there’s not a lot of wiggle room in the system from a FFP perspective. Since they’re already up against that €30M loss cap, if each team brings in someone new and pay them, they have to reduce their payroll elsewhere (or some other expense) to cover the expense of the new player or risk sanctions from UEFA. Their total spend can’t budge unless they drive more revenue or eliminate other costs.

But now consider the same scenario, except each team finds a player (or players) on one of the other 9 teams and is willing to pay €30M in transfer fees for the player(s). So everybody transfers a player around, and everyone pays a transfer fee, and suddenly each team isn’t sitting on a €10M loss, they each have €10M of net income (each club just logged €30M of immediate income and will expense €10M of amortized transfer fee this season, assuming a 3 year contract). They’ve all improved their profit/loss statement by €20M. Do this again the next year, and they’re all at €0 breakeven (another €30M transfers in minus €20M, or a year’s worth of €10M amortization expense on two separate €30M signings). Do it a third year, and they’re back to a €10M net loss and compliant with the cap (another €30M of income but they’ve now stacked 3 years of €10M amortization expense per player). The wage budgets are flat in this toy model because the players are just transferring between clubs and we’re assuming no revenue growth or payroll growth. Keep running this thing, and they stay there at a €10M loss, and as long as you hold all these other assumptions constant (no revenue growth, no wage growth) no matter how many times you repeat this loop, stacking the same amount of transfer fee income (€30M transfer fee) as transfer fee amortization expense (3 years worth of €10M on 3 separate deals) to perpetuity. If you add in more realistic assumptions like 6-10% revenue growth and payroll growth, the capacity to pay more and more transfer fees only increases.

[late edit years later: there’s an error of omission here. I assumed the players transferring hands here had been with their teams long enough such that any transfer fees previously paid for them had been amortized to zero, or there originally was no transfer fee paid at all. Once you transfer all these players around to infinity, you likely run out of unamortized players to transfer each year, such that you’re not getting the full income pop of the transfer fee revenue. Instead you’re getting that transfer fee less any unamortized previous transfer fees paid, whatever you get it]

Duh… I’m not going to win a nobel prize in economics by showing that money that just changes hands between 10 different clubs isn’t “consumed” —it just circulates— but it’s worth remembering just how unbounded the transfer fee activity is (someone’s amortization expense is actually 1/3 of someone else’s transfer fee income for every transaction in any given year) relative to how seemingly bounded the wages are.

More importantly, at a micro-level when an individual club president is under the gun on deadline day, trying to get a deal over the line, he might be first and foremost worried about the short term (the upcoming season). The entirety of any agreed upon annual player wage will hit as expense this year, while only a fraction of the agreed transfer fee will hurt him. On net, he might just decide to pay the higher transfer fee and sort the rest out next year …. Next year. I mean, hell. Maybe he can offload a player next year and lower his payroll to make room for the stacking transfer fee amortization. Maybe he can even get a transfer fee of his own next year for that player (and count it all as income!). He’d only need to pull in a transfer fee of a third of what he’s paying in now to live another day. It’s definitely gonna work out! Plus, revenues are gonna go up too! They always do, don’t th—

Scandalously (because math), a funny thing happens when you take the above toy model and just… increase the transfer fees being exchanged every year (by 10% or 20%, or 50%). I mean, maybe it seems obvious, but from an accounting perspective, the teams’ profit and loss statements just … improve(!), like every year. By the league collectively “growing their transfer fees rather than wages, ” their accounting incomes go up, and while their amortization expenses go up too, they lag behind the increased income… always (income up 30%, 1/3 of that up 30% as expense, 1/3 of last year’s lower transfer fee as expense, 1/3 of the previous year’s even lower transfer fee as expense).

So you have accounting conventions that at a micro level create an environment that encourages a GM who is in a pinch to just go ahead and pay the higher transfer fee and sort out the financial position later, and then at a macro-level… growing transfer fees (so long as they continue to grow) generate growing financial positions for the whole system (thanks to accounting)… On top of this, you have soccer regulatory bodies capping spending based on financial positions under the guise of “fair play.” And that’s before you account for actual economic growth, and the fact that accounting can actually spur actual economic growth and.. what am I doing.

Down the stretch

The basic headline of this post is just the affirmation that the value of a player’s services in monetary terms is not the transfer fee exchanged to convince his former club to terminate their contract with him. The value of a player’s services is best expressed as the wage he accepts from a club in exchange for offering those services. Wages are more reliably anchored in and worked out through a robust and overlapping labor market made up of contracts that span multiple seasons. By contrast, transfer fees are residual, presentist amounts clubs are willing to pay one another to terminate existing player contracts in order to agree new contracts with them (at generally higher wages) at the applicable labor market rates. Transfer fees are bounded on the low-end by the excess value a club enjoys by a player’s performance and therefore his market value exceeding the fixed wages they are paying him. Transfer fees are bounded on the high-end by very little aside from their reference to the authorized budgets allocated to the target players by prospective clubs, and the co-present negotiations of new player contracts and player wages (these amounts reducing the available authorized budgets), such that transfer fees represent what’s left over of the authorized budgets after the player wages are roughly agreed. Further, these transfer fees are untethered from “inherent values” due to accounting asymmetries which incentivize clubs at the macro-level to re-allocate higher shares of operating budgets from wages to transfer fees.

An “Absolute Unit” framework to transfers would further suggest that underpinning the amounts of authorized budgets allocated to target players is directly related to the club’s individual (and aggregate) assessments of a player’s projected goal contribution relative to his peers, and that the labor market and transfer fee mechanisms are just financial realities front offices must navigate while continuously and iteratively aligning and course-correcting the projections of their club’s competitive performance with their stated competitive objectives (set in goal difference).

Perhaps some tangible takeaways following these abstract wanderings are as follows:

If you’re a front office doing recruitment or squad management, don’t think about a player as a $/€ value that you hope to recoup or receive a return on upon their exit. Think of their services as inputs to a competitive process which works towards stated competitive objectives, the achievement of these objectives itself an input into a business process designed to create economic returns. Accordingly, think of your allocation to their total payroll (and acquisition) costs without regard to what you expect to recoup from them in transfer fees when they leave. This also means don’t avoid old players just because they may retire at the end of their contract, or otherwise depart without netting you a transfer fee. The point of the recruitment processes is not to generate “assets” which themselves generate income via transfer fees, but instead to sign players who will perform on the field and help the team win, allowing you to achieve commercial success through the primary channels of attracting eyeballs to your games and selling stuff to those eyeballs.

Along those same lines, if you’re a front office don’t do transfer strategy with the express strategy of buying low (young) and selling high. If you’re putting a premium on a player being younger, expect the “selling” club is also doing this, which means you’re not … winning the deal really by default if you “buy young.” Do, however, project a player’s development over the contract term, and to the extent you are able to allocate a lower share of your operating budget relative to his projected contributions to the team (due to the current stage of his development), that’s fine, especially if you are able to lock him in at a wage that reflects his current performance, not his future performance. If you continue to pay him these wages and his production increases, then he’ll want more money, which you can then oblige and sign him up for an even longer term (if that best helps you align with your competitive goals), or someone will pay you to terminate this “good” contract early, and then you continue to align your team projections and your operating budgets with your competitive goals. Understand that this calculation is in theory happening on the sell-side too, so … just don’t get too caught up in the whirlwind of expecting that because you paid $15M for an 18 year old, that you’ll necessarily be able to recoup that with a transfer fee received later. Instead it needs to make sense on the merits. The transfer fee will come only if these merits come good.

If you’re a front office, think long and hard about what a “sell-on” clause really is… What exactly is the potential income you are agreeing to participate in when you demand a percent share of the transfer fee attached to the next “sale.” If you accept a transfer fee in exchange for a player that goes on to play for 10 years at his next club and is so successful in his pursuits that he stays long enough to retire at the club, any sell-on percentage owed to you is zero. In light of this, are “sell-on” clauses actually a sensible way for clubs to share the risks and rewards of player development uncertainty with one another in transfers?

Similarly, if you’re a front office, think long and hard about any “buy-out” clause a player’s agent insists you put into a contract. Given the volatility and ephemeral nature of transfer fees, and their very time-bound context, agreeing now on a fixed amount to transfer a player for at any time during a 3-4 year contract period may be more of a handcuff to your roster building plans than you imagine. Again, your job is not to turn a profit on transfers, but to win.

For the rest of us not in front offices, should we perhaps consider resisting this urge to overly financialize the players as assets being bought and sold? Should we push back on assigning “market values” to them on a website as if they’re available for purchase in a catalog? Should we attempt to eliminate the “buy” and “sell” jargon that proliferates the media to such an extent that it is actively shaping the way front offices and agents think about transfers? Should federations and other regulators reconsider how they attempt to manage budget constraints amongst leagues given the financial bias towards volatility?

Yes?

Conclusion or something

A player’s value to the sporting director is how much he contributes in terms of team goal difference relative to other available players. A player’s value to a club president is this figure multiplied by how much team goal difference is worth to the club in monetary terms. A player contract’s value to a club is how much the player projects to contribute in terms of team goal difference over the remaining contract term relative to the budget allocated to him via his wage. A transfer fee is none of those things.

A club should have the right people and processes in place to measure the competitive value within the technical and sporting departments, and they should have the right people and processes in place to measure the economic value within the business operations departments. Then, those departments should talk to each other regularly.